“How much should I charge for my product or service?” – If you’re among the people asking themselves this very question, I have to break it to you – there is no easy answer. I am, however, able to guide you through the results of research which will help you in establishing a good pricing strategy.

You are pricing yourself too low

Let’s start with the basics: If you’re putting your own services (or products) on the market, you’re probably pricing them too low due to two reasons:

- You’re doing that which you love. Therefore, you consider what you do as pleasant. Imagine you love mowing your lawn and absolutely hate doing the dishes. You are willing to pay more to have someone do your dishes for you (because you loathe the chore) than to have them mow your lawn, right? In consequence, if someone asks you how much you would charge for an hour of lawn mowing… you’ll name a lower price.

- You’re good at what you do. While deciding on the pricing of our services, we often take time as a critical factor. A lawyer who charges $1,000 for a document which he prepared in 10 minutes is ripping you off. If the same material took two days to write up, it could easily cost $1,000. Try to remember how furious you were when the doctor charged you some ludicrous sum for a visit, and when he finished with you, all you could think of was that it took only ten minutes! Hence, you also have quarrels about charging a customer a thousand dollars for updating his website, knowing that it will only take you twenty minutes.

These two factors coalesce into what psychologists describe as negotiating with yourself. Before setting out for a meeting, you convince yourself to drop the price at least a little bit. You begin the conversation by offering a discount – or quite simply, your prices are lower than they should be from the very beginning. How should we go on about this?

- Ask somebody else to negotiate the prices for you. If you’re able to do so, it’s by far the most comfortable option. An “outsider” who knows how much your services are worth on the market, doesn’t have as strong of an emotional reaction towards your customers as you do.

- Negotiate with a note in hand. Be honest with your calculations on how much your services are worth, what are your costs and how much you want to earn. Write down the results on a sheet of paper and take it with you when sitting down to negotiations. Let it play the “bad accountant” role – you should even set some form of punishment for yourself should you go below the sum you jotted down. If it turns out you’re dropping prices too often, go back to the drawing board and review your calculations.

Your customers are more elastic than you think

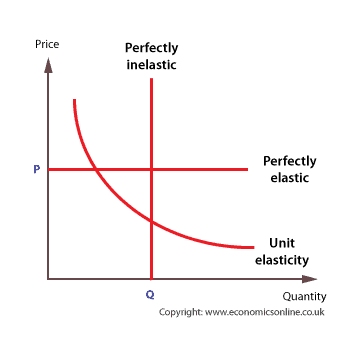

Do you know what the “price elasticity of demand” is? It doesn’t sound too appealing, but it’s an incredibly important factor when you design your pricing strategy. It shows how the demand for your products changes should you change your prices. In other words: If you raise your price by X percent, what percentage fewer clients will still buy from you?

A staggering majority of entrepreneurs (since the task doesn’t belong solely to the area of marketing) doesn’t measure and analyze the price elasticity of demand. The effect? They earn less than they could with the same amount of work. Look for yourself:

You run a language school. One term costs $1,000, and you have 80 customers. You earn $80,000 per semester. What will happen if you raise the price up to $1,200?

- If no more than 13 customers leave… you must raise your prices. This is due to the fact you’ll earn more having 67 customers paying $1,200 than while having 80 customers paying $1,000

Do you know what the most interesting part is? In many cases, the drop in customer level will be exactly… zero. If you don’t operate on the border of price elasticity (you price yourself lower due to the reasons I mentioned above), your customers will be ready to pay you more.

OK, so how do we design a pricing strategy?

A rounded price ($500) or one with a nine at the end ($499)? Or something else entirely ($473)? The price of your products or services influences price elasticity. If that wasn’t enough, the way you present the price also matters! Let us move on to the issues of the psychology of pricing strategy.

A pretty price

Take prices with a nine at the end. The nine itself doesn’t matter. Research shows that the most important is the leftward most number. If during price reduction the price dropped from $430 to $390, such a reduction is perceived as more attractive (will gain you more customers) than one where the first digit remained unchanged i.e., from $450 to $410. Even though it’s the same amount of dollars!

If that wasn’t enough, Keith Coulter conducted research which showed that the effect is amplified if the cents are in the fine print. Off to redo our price lists!

Note, however, that the effect of a pretty price works mainly on things we buy due to rational reasons (needed or necessary products), for example, bread, milk, a new school backpack or a winter jacket. If you’re selling things we purchase due to whims, you’re better off using a different pricing strategy, namely prestigious prices.

Prestigious prices

While shopping for luxury items (gaming consoles, sweets, a dinner in a restaurant) rounded prices such as $500 rather than $499 work best. Why? Research on this matter has been conducted by Kuangije Zhang and Monica Wadhwa. According to them, rounded numbers increase the “cognitive ease of processing.” Simply put, rounded numbers feel better and are easier to wrap our heads around.

While we’re at the ease of processing – prices with fewer characters or symbols (1400 instead of $1,400) are also easier to take in. And my favorite part of the research – which one “sounds cheaper”? One thousand five hundred or fifteen hundred? Prices with fewer syllables are perceived as lower. Perhaps we should charge $28,50 (5 syllables) instead of $27,70 (7 syllables)?

Among the research on cognitive ease and prices, I have my favorite: it was proven that a factor which spurs us into shopping is… the price matching our age! A consumer celebrating his thirtieth birthday should be offered a selection of products for $30!

Before you go on to rounding your prices, there’s one more thing to note concerning very expensive products.

Unit prices

There are products which customers perceive as “units” — bought individually, in small quantities and quite rarely at that. A house (or the architectural design of one), a website design (personalized not out of a template) or a car with custom equipment. In such cases, the price shouldn’t be a template either. Website design for $3,990 sounds a lot cheaper than a website for $4,130

A unit price offers the impression of uniqueness — for which the customers are willing to pay. It suggests that we took into account a few modules or elements and that neither the product nor the price is a template. While we’re talking about packages and modules…

Pricing strategy: package deals

When buying a car for $134,700 (you know, unit price), it’s much easier to justify throwing in that winter package for an extra $9,000 rather than “winter tires for $3,000”, “heated seats for $3,000” and a “towing hitch for $3,000”. In the second case, the customer has to make three individual decisions, whether to buy something or not. In the first, all it takes is one decision – and the price of $9,000 doesn’t seem so high when compared to the cost of the whole car.

It doesn’t seem so high due to the Weber-Fechner law, which states, that even if the price changes are fluid (raised by a single dollar), customers will still notice the changes in segments. Initial changes won’t affect them at all, but if you exceed the segment’s threshold, the price starts to sting. When it comes to price changes, the average worth of a segment is about 10%. If you increase your prices by an amount within 10%, chances are your customers won’t even notice the change. All that’s left is the matter of anchoring…

How do customers compare prices?

A $90 “Shrimp Feast” at a restaurant (the product is a luxury item, that’s why we use the prestigious, remember?) looks expensive… until we pit it against a “Shrimp Extravaganza” for $290. Our brain has trouble processing numbers without context. That’s why instead of assessing the worth directly, it often tries to compare it with something. “Anchoring” is an effect in which we compare something with things in its closest vicinity. Make the comparison easier and reap the rewards.

As the people at The Shopping Channel like to say, “But that’s not all!” What if we were to add a third option to our menu?

- Shrimp Feast $90

- Shrimp Feast Premium $120

- Shrimp Extravaganza $290

What do you think will happen? People will start choosing the “Shrimp Feast Premium” more often. Aside from anchoring, we observe something that Daniel Kahneman pointed out as a “minus A rule”. While comparing three products, our brains tend to cast aside the one which is more difficult to compare with the rest (In this case the “Shrimp Extravaganza” seems something completely different than the other two “feasts”) and directs the choice to the remaining two. In the case of luxury items, the more expensive ones win far more often.

Time over money

Do you want customers who purchased your shrimp feast to come back for more? Don’t mention money! In her studies, Jennifer Aaker proved that people are willing to buy more if we remind them of the time they spent with our product or service rather than the money they saved on it. That’s why “Remember the fun you had with your friends sharing our shrimp feast?” is a far better pitch than “Remember the 30% you saved on the shrimp feast?”.

Speaking of time – a high price spread throughout a time period works better, too. Would you prefer to spend $168 for a year of Premium Netflix access for a year or just $14 per month? That’s why certain companies inform customers about a monthly subscription plan… yet charge them for a full year on purchase.

Designing the pricing strategy isn’t an easy task, but knowing how people react to prices and how they assign worth enables you to increase your income without undergoing any internal changes within your company. Hence… it’s worth it! Good luck!